Windermere: Nature connection & swimming

Taylor Butler-Eldridge's research on the changing environment of outdoor swimming at Windermere

This week is an extended edition all about swimming.

I spoke to Taylor Butler-Eldridge about his four-year PhD research on swimming & Windermere to unpick some of the challenges.

The activity is one of few sports that is heavily reliant upon the surrounding environment and we as swimmers have an effect on the water even in the most miniscule examples, such as microplastics from our swimwear, chemicals from suncream, and contamination of non-native species (check, clean, dry).

We couldn’t cover all of these subjects, but a few of the most common ones in his research were unpicked. As you might expect, water quality and pollution is a common one and unfortunately is synonymous with outdoor swimming.

Our chat follows the Outdoor Swimming Research Forum which Taylor hosted in September. It was a fantastic event which featured presentations from researchers on their work and discussions around areas for development. Presentations included a wide range of subjects such as Joyce Harper’s research on the benefits of cold water swimming for menopause and menstrual symptoms; Ronan Foley on swimming as a salutogenic practice; Heather Massey and Hannah Denton on swimming as a nature-based intervention for depression; Rebecca Olive’s research on swimming in ecologies; Elitsa Penkova’s study on whether antimicrobial resistance is a threat to public health, and many more.

One of the subjects we discussed on day two in relation to access and the huge challenges and pressures on our waters at present was should we swim at all, or should we give these places a rest from human activity? It was a bigger picture thought that has stuck with me ever since, and one that remains a theory rather than a reality.

Finally, Ged Dolan shares what he learned after 1,000 consecutive days of outdoor swimming.

Happy reading!

The challenges of outdoor swimming at Windermere

There’s a lot of information out there to tell us that outdoor swimming is good for us. Whether it’s for exercise, recreation and leisure, socialising with others, challenging your fears, or it’s just about getting outdoors in nature and the sensory experience, lots of us enjoy it.

Although the health benefits are real, outdoor swimming is one activity (including for exercise and recreation - wild swimming) that is vulnerable and has a knock-on effect to the surrounding environment from water quality, access, and what is living under the surface.

Most swimmers’ intentions are generally positive - for the personal health benefit as well as social connections - but new research shows motivations to swim can cause conflict with the surrounding environmental pressures of the lake. These challenges encourage us as water users to look inwards and ask difficult questions about how our practice has a ripple effect.

Taylor Butler-Eldridge digs into the complexities. Windermere was his first experience of freshwater swimming back when he was a University of Cumbria undergrad around 2016. Now as a PhD researcher, he spent four years studying Windermere and his wet ethnographic fieldwork included immersing himself with the regular swimmers and conducting 40 swim-along interviews.

“I had secured PhD funding before the heightened news of Windermere’s water quality,” he says. “I was vaguely aware of algal blooms, wastewater, plastic pollution and biosecurity before I started. But not to the extent of what I found during my research and what blew up in local and national news.

“The PhD evolved into this question around how swimmers were negotiating environmental health concerns, taking care of themselves, their communities and with these fragile fresh waters, but also who is taking care of swimmers.”

The research required diving into the site specifics, those influences, and the broader relational understandings of health. “It’s how these environments, the other freshwater species and factors influence, reciprocate and complicate each other, and that's why it takes nearly four years to write all of this,” he said.

Other than some clothing and equipment innovation, not much has changed in the practice of swimming across the last few decades, people have swum outdoors for centuries. But a lot has changed with the popularity and interest in it, and the sudden interest spike in pollution and water quality across the UK means the two topics run parallel to one another. However, Butler-Eldridge’s research found that people’s motivations to swim outweighed the murky reasons not to.

He says: “What's really clear at this stage, is that accounts of illness from potentially poor water quality conditions at Windermere are still anecdotal and minimal … [However], I don't dismiss health concerns for people, especially in our changing climates.

“Those concerns of cold water shock, after drop, hyperthermia, visibility, boat traffic, particularly inexperienced boat users and conflicting user groups and values they seem to dominate much more than the potential of getting illness for regular swimmers. I say regular swimmers because I can't speak on behalf of those that don't swim or avoid swimming at Windermere.

“There are stronger health motivations to swim and plenty of them often outweigh concerns of potential illness from, for example, a toxic blue-green algal bloom or pathogenic bacteria from wastewater. In the water, concerns of illness for swimmers are overpowered by direct bodily sensations from the water.”

He adds: “I would argue that it still lingers. It's still in the back of their mind, but they displace it to not disrupt their motivation to swim or even to not disrupt louder voices within the community that have strong opinions and dismissal of water quality.”

There is a strong sense of powerlessness when it comes to water quality. We can prevent litter, which is visual, from the side of the lake, but we can’t personally stop sewage from flowing into it and we can’t always see the wastewater as it’s under the surface. However, when talking about the environment, the topic of litter came up well before sewage with participants.

“That does also highlight tones of localism, hypocrisy, idolised users and user values, but also it reinforces perceptions of individual responsibility as well. We all carry a trace, and we want to pin it on somebody. I'm not saying that responsibility is evenly shared but there is some element of collective responsibility.

“If people don't feel a sense of hope that Windermere isn't all doom and gloom, they're not going to invest their time and energy and care into it.

“These issues aren't going away, but it's so interesting to see how these concerns have been there for a long, long time, but because more people are swimming and wanting to access these spaces, people are questioning what happens when you flush your toilet.”

Romanticising swimming

Another takeaway theme for Butler-Eldridge was the level of romanticisation of swimming. There’s also the visual ideal of what is a healthy lake, as not many of us seem to know.

“I found that the idyllic and strong visual associations towards perceptions of ‘nature connection’ and human restoration from swimming outdoors …. [people] simplify, separate and potentially mask responsibilities towards other freshwater species which are under significant pressure. This isn't just human concerns; this is what's living in the lake.

“What I found is that there's a clear lack of literacy in both how swimmers verbalise their relationships with the water, but also with other non-human elements. So weather, water, conditions, bird life, fish, other freshwater species, even bacteria - swimmers often fall on kind of very benign expressions, very romantic, very strong visual assumptions in how they perceive a healthy Windermere.

“Often people would be distracted by the view of the distant mountains, the sparkle of the sun reflecting off the surface, perhaps even less aggressive looking swans and less people too, which opens up another can of worms.”

Butler-Eldridge adds: “Tranquillity and the language around ‘nature connection’, is very romantic, very idolised - which I'm not judging or criticising - but it often cannot go beyond that. When talking about ‘nature’, there was a clear distinction of what that included, which seemed to be water, trees and mountains and ‘there's a swan, or there's a bird’.” But he admits: “It is difficult to talk while you're in the water, let's be honest.”

Swimming with care

Windermere is one of the most studied lakes in the world, and as England’s largest lake at 10.5 miles long it is also one of the busiest. It’s frequented by swimmers, boats of varying sizes, anglers, paddlers who must share the space, and that’s just the humans on the surface.

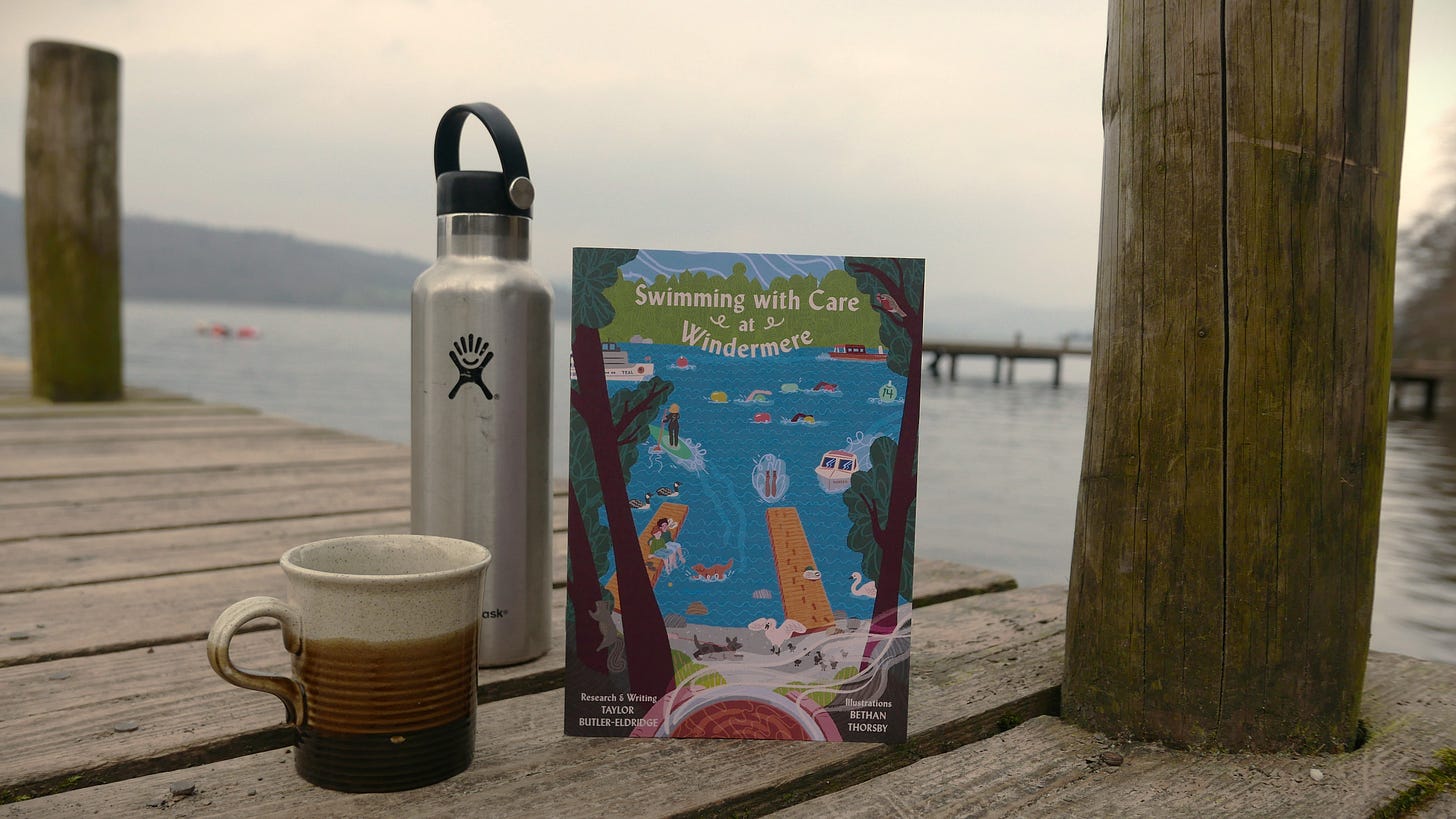

The idea of “swimming with care” and exploring what the word “care” denotes was brought up during his interviews. Butler-Eldridge and Cumbrian illustrator Bethan Thorsby created a zine delving into the positive and negative implications including care for yourself, each other and your surroundings.

Considering the need for ‘care’, and the already busy human activity on the lake, would it be better for Windermere if nobody swam, or there were fewer water users?

“Well, that's a big question,” Butler-Eldridge says. “That was something that came up in the research significantly. A couple of people talked about the need for less people, less users. Some said that they would happily avoid swimming at Windermere if it meant that it could give the lake a bit of a break.

“I strongly sense that when people say less people, they mean who - less boat traffic, inexperienced boat users, paddleboarders, infrequent users that have bluetooth speakers emitting different types of music. It's all very hypocritical.”

The unwritten rules go back to the idea of tranquillity and relationships with the water. Windermere is a shared space, most of us go down to the lakeside to have a good time, for a health or social benefit and there’s no rule that says music can’t be played by the lake, for instance.

“There are significant access concerns, perpetuated by uneven social and political structures so I would encourage regular swimming communities to question their own privileges and speak to non-swimmers, especially people of colour, those with disabilities, illness, and those who are stigmatised or perhaps nervous and fearful too.

“We need to continue finding ways to support people getting into the water and also build ways of assessing when and where not to swim. That includes biosecurity concerns (check, clean, dry) which seem to have been drowned out recently from heightened attention on sewage.”

You can read Taylor’s paper here. Catch up on the forum here. Find his work (Swimdermere), and grab or download a free copy of the zine.

Taylor’s swimming guidance

No two swims are ever the same. Take your time, breathe, feel it out, and get out before you feel too cold. Our bodies and environments are always changing and in relation to each other. Outdoor swimming can be positive and it can be negative.

There are moments of elation, joyfulness, playfulness, socialisation, community exercise, a sense of building self-efficacy and confidence, especially those in recovery or those negotiating illness, grief, anxiety, depression, and trauma. But there are also plenty of times that you could regret having a swim.

Winds can rise, water clarity, blue-green algae, and other bacteria levels can fluctuate alongside the social conditions, changing weathers and climates. And it might just feel too cold, or you just might not feel it. Listen to that and try and assess your own needs.

Try not to be egged on by others, and if you're swimming distance, wear a tow float and a bright swim cap to improve visibility.

It's also OK to miss a swim, to stay closer to the shoreline and to get out earlier than you might have originally intended. And it's OK to wear a wetsuit.

What I learned from 1,000 days of swimming

By Ged Dolan

Almost three years without missing a day. 20 continuous strokes, that was my rule for a swim to count towards my goal as this was always a swimming rather than dipping challenge.

I chose 20 strokes as it's a typical pool length, and while it doesn't sound much, 20 strokes in frozen depths of winter could feel like swimming across an icy expanse.

This challenge took me to all the major lakes of the Lake District, many high mountain tarns, rivers, urban waterways, wild Atlantic beaches and Alpine waterfalls pools, and taught me a lot about myself in ways I didn't expect.

Resilience: I'm far more resilient and determined than I ever thought I was. Finding time to swim every day, regardless of the weather or how I was feeling became so normalised to me that it's only since I've completed this challenge that I realised just how strong my will and determination can be. Swimming at 3am in the dark before going to airports, snowy hikes through frozen forests when the roads were impassable were done without question.

Routine: This is important to me. Doing something every day, without question and without overthinking overcomes decision fatigue and self-doubt - something I'm prone to. It was never 'should I swim today?’ just 'when should I swim today?'

Risk: I'm a much bigger risk taker than I thought I was. Swimming outdoors is an inherently risky proposition, especially in winter. And while risks should be respected and appreciated, they also shouldn't be preventative. The 'rules' of outdoor swimming say never swim alone, but the vast majority of my 1,000 swims have been alone. Had I followed the guidance, I would never have swum outdoors.

Friendship: I began this challenge as an introverted solitary swimmer; by day 1,000 I had an amazing group of friends who came to celebrate my final swim. I've met so many great people during this challenge from a wide range of diverse backgrounds, and had so many awesome adventures as a result of this. Before this challenge I didn't really appreciate the value of friendships and shared interests. Cold water is addictive, and stripped of ego (and clothes). Everyone is equal in the water.